Startup Neurophos has secured $110 million to develop technology that aims to address the shortcomings of previous photonic-computing companies. The company employs tunable metamaterials to improve computational density and to enable dynamic configuration of the optical transfer function. Additionally, reflectors fold the photonic pipeline, locating optical inputs and outputs in the same plane, which enables placing the photonics atop a chip.

Metamaterials have unusual characteristics that depend on their structure instead of their chemical composition. Neurophos describes its material as a planar metasurface that manipulates the wavefront of light. The company has withheld details of its metasurface but states that it contains only standard silicon-foundry materials. We speculate that these include the metals and dielectrics found in CMOS chips. An electric field applied to the dielectric alters its optical properties, enabling its reprogrammability.

The Neurophos technology extends Duke University research and earlier work conducted by affiliates of Intellectual Ventures (IV), a patent troll that also performs R&D. Neurophos counts Nathan Myhrvold, the cofounder of Intellectual Ventures, among its advisors. The company’s cofounders, Patrick Bowen and Andrew Traverso, were both Duke researchers and have previous ties to IV/Myhrvold-backed companies.

RTFWP

A white paper on the Neurophos website discusses its technology, including the advantages of metamaterials and the company’s folded-pipeline trick. Scale is the primary plus. Whereas past photonic-computing startups had small (e.g., 64 × 64) multiply-accumulate (MAC) arrays, Neurophos promises a 1,024 × 1,024 array. Without this scale, there’s little gain from employing photonics instead of conventional digital electronics.

Previous startups also focused on accelerating convolutions. By contrast, Neurophos emphasizes large, general systolic arrays, which can process large language models (LLMs). However, this difference could be a byproduct of the era. Before 2017, most AI efforts focused on convolutional neural networks. Since then, transformer-based LLMs have become predominant. Even early Neurophos efforts tackled convolutions.

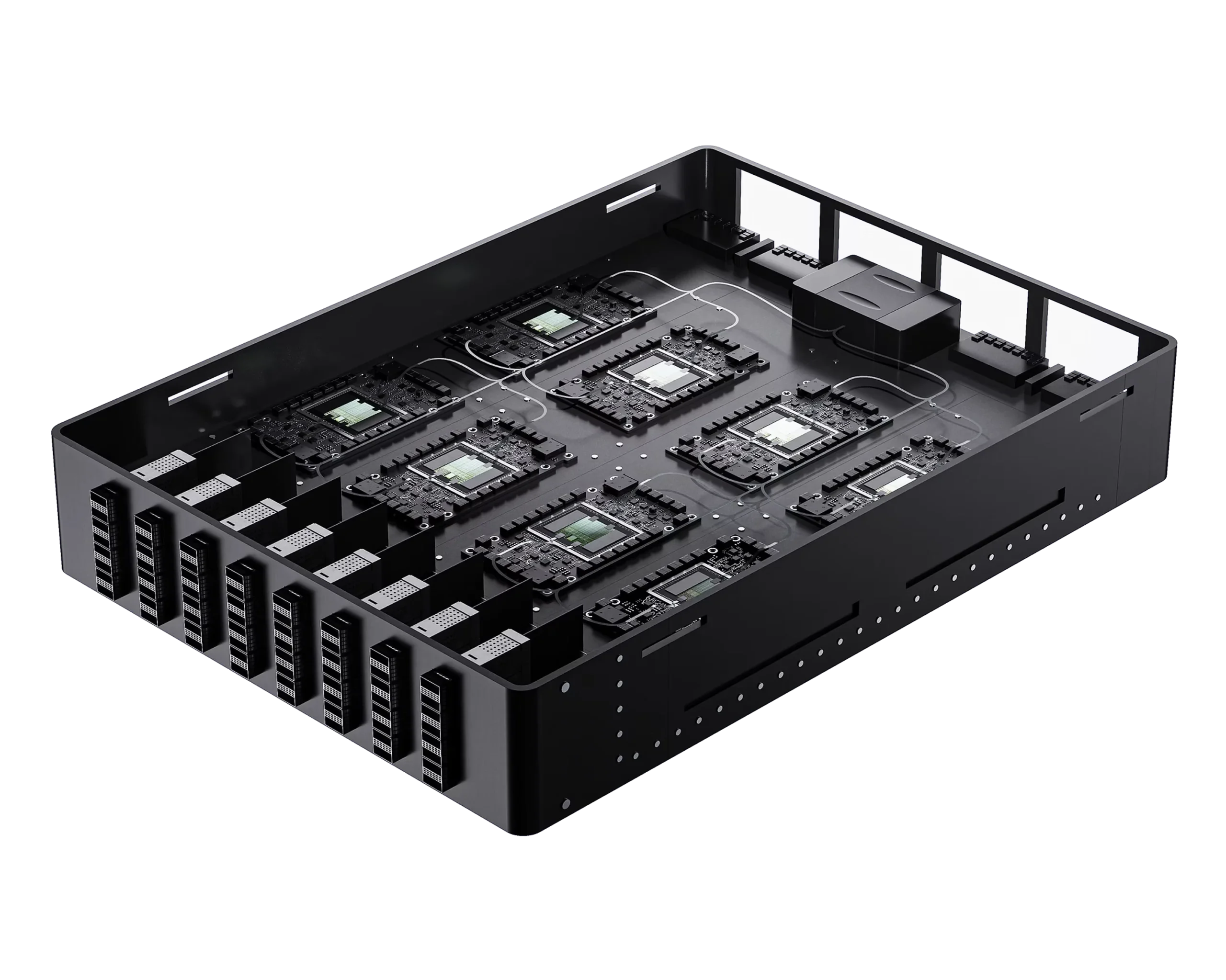

A further issue is multichip scaling. Neurophos hasn’t described it but is pre-selling a server. Renderings of the system show eight photonic-computing modules, which it calls optical processing units (OPUs). The company rates the system at 2,000 PFLOPS on FP4 operations and 1.6 PFLOPS for FP16, enabled by the OPU’s 56 GHz clock speed. By comparison, the 72-GPU Nvidia GB200 NVL72 rack-scale system delivers 720 FP4 PFLOPS and 360 FP16 PFLOPS. The OPU’s greater raw performance requires a fraction of the power, too: 10 kW compared with 1.2 kW per Nvidia GPU plus power for the myriad other NVL72 components.

Bottom Line

The combination of power efficiency and throughput is the OPU’s key selling point. Barring revolutionary technology like Neurophos promises, power and cost will limit AI scaling. Hurdles remain. The company must fulfill its promises and surmount the challenge that stymies other AI-accelerator companies: software.

The Byrne-Wheeler Report recently discussed Neurophos: