The tachyon is a faster-than-light particle, which cannot exist without violating known physics laws. Tachyum is a company promising to perform as well as a CPU, GPU, or NPU, which also shouldn’t be possible. Also threatening its existence, the company sued Cadence in 2022 after finding blocks (IP) licensed from the EDA giant were deficient. The parties settled in 2023, but the startup missed its initial product window and delayed its subsequent processor.

Tachyum continued to develop its second generation, evolving it from a 256-core 5 nm design to a chiplet-based 2 nm processor with four times the CPUs. Named the Prodigy Universal Processor, like the original 7 nm Tachyum project, the new design is to sample in 1Q 2027. Planned SKUs integrate one, two, or four dice and offer 32–1,024 total cores.

Along with the processor, Tachyum has also defined a memory module (DIMM) that raises throughput compared with standard DIMMs while still using standard memory ICs. The company also defines new AI data formats, extending its earlier work on four-bit floating-point data and a nominally two-bit format to include a new 1.5-bit type.

Microarchitecture

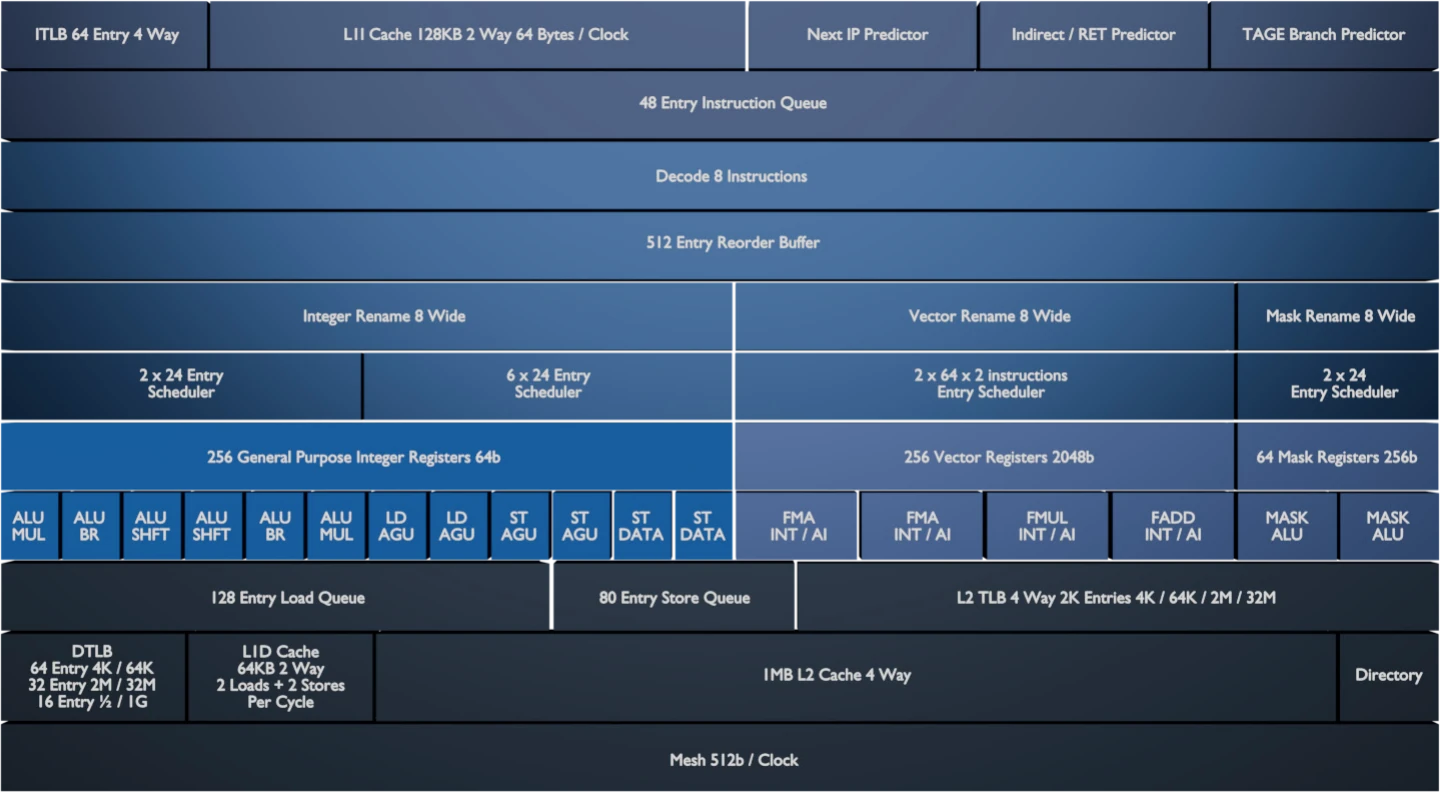

Designed to excel at CPU, GPU-compute, and AI workloads, Prodigy’s microarchitecture resembles that of a CPU. Like most high-performance CPUs, it includes integer and vector/floating-point cores. The latter is large, capable of issuing 4 instructions per clock to 512-bit data paths. As with RISC-V CPUs, Prodigy decouples architectural vector length from the physical data-path size, supporting vectors from 256 to 2,048 bits. Completing operations on vectors larger than 512 bits requires multiple cycles.

Holding 256 2,048-bit items, the register file is large. Integrated within the vector units are matrix units. These operate on 2,048-bit matrices, which Prodigy stores in the vector register file, as Figure 1 shows.

Figure 1. Tachyum Prodigy implements a CPU microarchitecture with vector extensions. (Source: Tachyum.)

Tachyum also separates mask registers and function units from the vector data path. Masks are a common way for SIMD architectures to implement conditional execution without branches. Each mask register is 256 bits, twice what is needed to mask four-bit data because the registers also double as exponents in microscaling formats (e.g., FP4).

Instruction Set Architecture

Instructions are simple, like those of a RISC architecture, and 32 or 64 bits. A few other RISC instruction sets have different lengths, but typically they incorporate a 32-bit base and a 16-bit extension for code density. We expect larger (e.g., 64-bit) extensions to become more popular. Unlike RISC designs, Prodigy also includes ALU instructions that access memory.

Tachyum uniquely links instruction set architecture (ISA) and microarchitecture to increase clock rate. Instructions hint at which function unit handles an operation, specifying, for example, that an add instruction should execute on an ALU local to the one that handled a preceding operation. The locality concept is unusual (the Condor Cuzco is slightly similar) and enables the propagation time between local units to govern clock rate. By contrast, other CPUs require the clock to be slow enough to allow propagation between the furthest apart units. Prodigy’s drawback is that it can only execute dependent instructions during consecutive cycles if they run on local ALUs. Otherwise, propagation requires an additional cycle.

With the propagation path limited to neighboring units, the company expects even the biggest Prodigy SKUs to run at 6.0 GHz compared with 2.0 GHz for the largest Intel Granite Rapids Xeon. The Xeon’s limit, however, is power. Intel’s PC processors integrate similar CPUs and achieve 6 GHz. The open question is: how much more power efficient will Prodigy be?

AI Processing

As noted above, the four vector units each integrate with a matrix-multiply-add unit that handles 2 kb matrices, storing matrices in the vector register file. This approach differs from matrix extensions from Arm, IBM, Intel, and SiFive that rely on a discrete matrix-math block. Although RISC-V defines an approach similar to Tachyum’s, it’s positioned for designs requiring low-cost AI processing.

Prodigy supports common data formats and then some, with the exception of the oddball FP6 type. The four-bit Tachyum AI format (TAI) is also supported. Like other low-precision floating-point formats, it’s a block type that associates a scale factor with a group of values. It differs from the MXFP4 standard by halving group size to 16 and using a 32-bit instead of an 8-bit scaling factor.

Unusual Data Types

Tachyum supports an “effective” 2-bit format (TAI2) that relies on software-based pruning (and, presumably, Prodigy’s sparsity mechanisms) to zero out half the parameters in an FP4 neural network. It also supports an effectively 1.5-bit format, which entails quantizing model parameters to ternary digits (–1, 0, and +1). Mapping these “tits” to binary hardware requires two bits, with one of the 22 states unused. But squeezing tits together and pruning, as done with TAI2, saves space, yielding the effective 1.5 bits per value.

Like Nvidia’s GPUs, Prodigy supports 4:2 structured sparsity, the zeroing of half the values in a group of four. It also supports 8:3 sparsity and an additional, more flexible, sparsity approach. We speculate that the latter encodes the packing of nonzero values in a structure separate from the data.

System Design

Tachyum plans to offer Prodigy in three packages, varying in the number of supported DRAM channels, chiplet quantity, and physical size. It will collaborate with partners on motherboards, supporting up to 16-socket designs. Motherboards holding up to eight standard (medium-size) packages will fit in a 19-inch rack. Motherboards with eight high-performance (large) sockets and those with 16 standard sockets will require a wide rack.

Multisocket operation requires a chip-to-chip interconnect, which Prodigy provides through the UALink protocol over 224 Gbps serdes. Prodigy will also support PCIe 7.0, which provides 128 Gbps per lane. Lane count varies by processor model; 128 and 96 lanes are the most common configurations. The PCIe ports also support CXL 3.2 for clusters having large memory pools. Prodigious memory bandwidth comes from 24 DRAM controllers supporting DDR5 MRDIMM 3.0 at 17.6 GT/s. The medium-size package reduces the number of memory channels to 16, yielding 256 channels in a 16-socket system.

TDIMM Memory Module

To facilitate packing memory into a system, Tachyum has defined an alternative to standard DDR5 DIMMs, the Tachyum DIMM (TDIMM). It makes the following changes to double per-DIMM bandwidth while still employing standard DDR5 components and preserving DIMM size:

- Narrowing pin pitch from the 0.85 mm DIMM standard to the 0.5 mm SO-DIMM standard used in laptops.

- Using the narrower pitch to double the number of data pins per DIMM to 128.

- Employing the same number of ECC bits despite widening the memory.

- Reducing the number of DQS (strobe) pins by four to 36.

- Populating DIMMs with ×8 instead of ×4 DRAM chips.

On the processor/SoC side, the DRAM controller must be adapted to support the wider data interface—144 bits of data plus ECC, compared with 80 bits. The changes raise per-DIMM bandwidth to 281 GB/s. Consequently, a 24-channel Prodigy provides 6.7 TB/s of peak memory bandwidth. By comparison, Nvidia Rubin’s peak memory bandwidth is 22 TB/s, achieved by employing HBM4, which limits memory capacity.

Bottom Line

Prodigy and the TDIMM both demonstrate a common Tachyum characteristic: balancing convention and innovation. Prodigy reflects a conventional CPU architecture adapted to achieve higher clock speeds, and the TDIMM likewise adapts standard DRAM and DIMM technology to double throughput.

Providing not-quite-standard technology to raise performance could put off many customers, however. In particular, Prodigy implements a unique instruction set. Recompiled open-source software is available, but incompatibility with the status quo delayed Arm’s adoption in the data center and still holds back RISC-V. Tachyum mitigates this problem with x86 emulation software, but that lessens its performance advantage and is unlikely to be enough to attract mainstream data-center customers.

Execution is a further concern. Tachyum started its first design in 2016, targeting a 2019 tapeout. The company then created a new design, the original Prodigy, before the Cadence litigation precipitated a further delay. The new Prodigy is more promising, and the company has secured funding and a $500 million purchase order, but its sample date is still a year out.

However, Tachyum’s advantages may win additional backers. Its floating-point throughput could attract HPC customers, who are less reliant on a software ecosystem. The AI boom could also prove beneficial. Because of its universality, Tachyum serves both host and NPU/GPU functions, simplifying system design. Moreover, its CPU-based programming model simplifies software development. In summary, Tachyum is innovative, and, like the tachyon particle, promises speeds thought impossible. And, like the tachyon, Prodigy will have to be seen to be believed.

For more information, go to Tachyum’s web site to access white papers of various vintages, including this one comparing the new Prodigy to a previous iteration.